- Figure 1

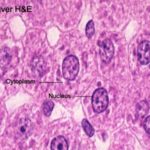

- Figure 2

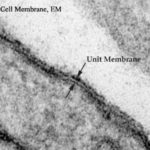

- Figure 3

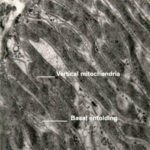

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

- Figure 14

- Figure 15

- Figure 16

- Figure 17

- Figure 18

- Figure 19

- Figure 22

- Figure 21

- Figure 22

- Figure 23

- Figure 24

- Figure 25

- Figure 26

- Figure 27

- Figure 28

- Figure 29

- Figure 30

- Figure 31

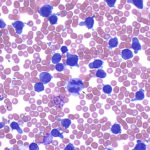

![]() The cell is the structural and functional unit of all tissues

The cell is the structural and functional unit of all tissues ![]() . It consists of a mass of protoplasm divided into nucleus and cytoplasm. The cytoplasm is the part of protoplasm located around the nucleus designed to perform synthetic and metabolic activities. It consists of structurent-weight:700″>Cytoplasmic matrix.

. It consists of a mass of protoplasm divided into nucleus and cytoplasm. The cytoplasm is the part of protoplasm located around the nucleus designed to perform synthetic and metabolic activities. It consists of structurent-weight:700″>Cytoplasmic matrix.

The cytolplasmic matrix (cytosol) is the non-organelle component of the cytoplasm occupying the intracellular spaces between organelles and inclusions. It contains any soluble proteins, lipids, carbohydrates and small ions.

Cytoplasmic Organelles

They are permanent, living cytoplasmic structures that perform specific functions. Two types of cytoplasmic organelles are recognized: membranous and non-membranous organelles.

- Membranous organelles

The membranous organelles are cytoplasmic organelles that posses a bounding membrane of their own and they include cell membrane, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, and peroxisomes.

Cell membrane

The cell membrane (plasmalemma or plasmamembrane) is the outer membrane of the cell that acts as a barrier between its internal and external environment.

With light microscope (LM) it is too thin (8-10 nm) to be seen.![]() The cell boundary that is often seen is mainly due to condensation of cytoplasm on the inner aspect of the cell membrane, condensation of the stain (such as silver or PAS) on the carbohydrate-rich coat and obliquity of the sections.

The cell boundary that is often seen is mainly due to condensation of cytoplasm on the inner aspect of the cell membrane, condensation of the stain (such as silver or PAS) on the carbohydrate-rich coat and obliquity of the sections.

![]() With electron microscope (EM) it appears as a trilaminar structure consisting of outer and inner electron-dense layers separated by an intermediate electron-lucent layer.

With electron microscope (EM) it appears as a trilaminar structure consisting of outer and inner electron-dense layers separated by an intermediate electron-lucent layer.

The molecular structure of the cell membrane

The most recent and currently acceptable model for the cell membrane is the

Fluid mosaic model

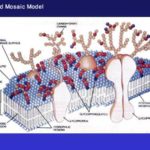

![]() According to this model, the cell membrane is made up of three major components phospholipids, proteins and carbohydrates.

According to this model, the cell membrane is made up of three major components phospholipids, proteins and carbohydrates.

The phospholipids molecules form a central bimolecular layer. Each molecule is formed of two ends; polar or hydrophilic (has affinity with water) end, and non-polar or hydrophobic (has no affinity with water) tail. The phospholipids molecules are arranged with their hydrophilic ends are directed outward, while hydrophobic tails are directed inward toward the center of the membrane.

The protein is the second major constituent of the cell membrane. The protein molecules are arranged as globules moving freely within the lipid layer. Two types of protein globules are recognized; intrinsic or integral protein and extrinsic or peripheral proteins.

The intrinsic proteins are firmly attached to the lipid bilayer. Some of them extend throughout the entire thickness of the membrane and constitute transmembrane channels for the passage of water-soluble ions and molecules

The extrinsic or peripheral proteins are only partially embedded to either aspects of the membrane.

The carbohydrate fractions are conjugated with the protein (glycoprotein) and lipid (glycolipid) molecules of the cell membrane. These glycoproteins and glycolipids project from the outer surface of the cell membrane as cell coat or glycocalyx ![]() .

.

Functions of the cell membrane

The cell membrane is the part of the cell that regulate the exchange of molecules and ions between its internal and external environment. This occurs by several ways:

- Passive Diffusion: this involves the entrance of small molecules into the cytoplasm. It depends on the presence of a concentration gradient across the plasmalemma (e.g., diffusion of lipid soluble substances, oxygen, CO2, water and small ions).

- Facilitated Diffusion: this type of diffusion is also concentration-dependent and involves the transport of large water-soluble molecules such as glucose and amino acids. It requires the presence of carriers to which the molecules have to bind in order to pass through the plasmalemma.

- Active Transport: this process requires the utilization of energy provided as ATP. (e.g., sodium-potassium pump).

- Selective transport: it depends on the presence of specific cell surface receptors to pick up specific molecules into the cytoplasm (e.g., hormones).

- Endocytosis and Exocytosis

Endocytosis involves either the engulfment of solid particles (phagocytosis) or minute droplet of fluid (pinocytosis). The engulfed material is surrounded first by cytoplasmic extensions called pseudopodia. When the particles become completely surrounded, the plasma membrane fuses and the membrane surrounding the engulfed particles forms a vesicle, known as a phagosome or endocytotic vesicle, which detaches from the cell membrane to float freely within the cytoplasm.

Once the phagosome enters the cytoplasm it fuses with the lysosomes and their contents are subjected to enzymatic digestion.

- Exocytosis

Exocytosis (Exo = out) is the process by which some membranous vesicles located within the cytoplasm fuse with the plasma membrane and release their contents outside the cell. It occurs in many secretory processes.

Functions of the cell coat (Glycocalyx)

- Mechanical and chemical protection the cell membrane.

- Aids in the induction of immunological (antigen-antibody) response.

- Site for binding of hormones.

- Shares in the formation of intercellular adhesions.

- Contributes to the formation of the basement membrane.

- Cell recognition.

Other functions of the cell membrane include

- Transmission of nerve impulses in muscle and nerve cells.

- Myelin sheath formation (Schwan cell around peripheral nerves).

- Share in the formation of microvilli, cilia, flagella and cell junctions.

Mitochondria

Mitochondria are membranous organelles involved primarily in cell respiration and energy production.

With LM , they appear as granules, rod-like or thread-like. Their size rage from 5-10 mm length and 0.5-1 mm in diameter. The number is highly variable according to the energy requirements of the cells. Liver cells (active cells) contain as many as 1000 mitochondria. Small lymphocytes (inactive cells) contain very few.

They are motile organelles and localize at intracellular sites of high-energy requirements such as basal regions of ion-transporting cells![]() .

.

They could be selectively stained with iron hematoxylin, Janus green B in supravital staining of living cells.

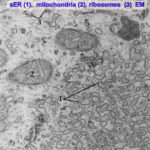

![]() With EM, they appear as ovoid or elongated structures bounded by two membranes. The outer membrane is smooth. The inner membrane is thrown into folds called cristae projecting into the inner cavity that is filled with an amorphous substance called matrix. The number of the cristae seen in mitochondria is directly related to the energy requirement of cell .

With EM, they appear as ovoid or elongated structures bounded by two membranes. The outer membrane is smooth. The inner membrane is thrown into folds called cristae projecting into the inner cavity that is filled with an amorphous substance called matrix. The number of the cristae seen in mitochondria is directly related to the energy requirement of cell .

The inner membrane is covered with tiny spherical projections about 9 mm in diameter supported at narrow stalks. These are called inner membrane spheres or elementary particles, and are believed to represent an enzyme known as F1, which couple electron transport to the phosphorylation of ADP.

The mitochondrial matrix is also contains many electron-dense granules called matrix granules that are the sites for Ca++ ions storage. The mitochondrial matrix contains DNA and RNA that explain the mitochondrial ability to grow, divide and synthesis some of their proteins.

Functions

- They house the chains of enzymes that catalyze reactions that provide the cells with most of its ATP (adenosine triphosphate).

- On demands, the ATP yields its high-energy phosphate bond to another molecule and become transformed into ADP.

- Within the mitochondrial matrix, ADP is transformed again into ATP. These processes take place within the mitochondrial matrix and inner mitochondrial membranes.

- The matrix contains enzymes of Krebs cycle and fatty acid oxidation. The inner membrane contains the cytochromes and the enzymes involved in ATP production.

- Due to their role in energy production, the mitochondria are likened to powerhouses of the cells.

- Participate in regulation of calcium level within the cytosol.

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

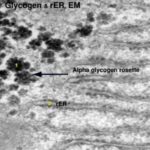

The Endoplasmic reticulum (Endo=inside; plasm=cytoplasm; reticulum = network) is an irregular network of branching and anastomosing tubules, cisternae and vesicles. Two types of ER are recognized, rough and smooth.

Rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER)

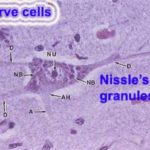

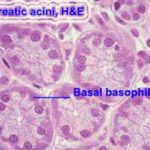

The rough endoplasmic reticulum is a membranous organelle concerned principally with synthesis and secretion of proteins. It is called rough due to the presence of large number of ribosomes attached to its limiting membrane. With LM, it appears as basophilic cytoplasmic areas that are referred to as the ergastoplasm or chromidial substances. The cytoplasmic basophilia may be diffuse (plasma cells), localized (pancreatic acinar cells)![]() or arranged into clumps (Nissl granules in nerve cells)

or arranged into clumps (Nissl granules in nerve cells) ![]() . Aggregates of rER appear basophilic mainly due to the presence of ribosomes on their outer surface .

. Aggregates of rER appear basophilic mainly due to the presence of ribosomes on their outer surface .

With EM, it consists of an anastomosing network of tubules, vesicles and flattened cisternae that ramifies throughout the cytoplasm. Much of the surface of the rER is studded with ribosomes giving the reticulum a rough or granular appearance.

Functions:

- Synthesis of proteins for extracellular use (secretory proteins, lysosomal proteins and membrane proteins).

- Glycosylation of proteins to form glycoproteins.

Smooth endoplasmic reticulum (sER)

The smooth endoplasmic reticulum is a membranous organelle consists primarily of a network of branching and anastomosing tubules and vesicles.

It differs from the rER in that its limiting membrane is smooth and devoid of ribosomes. With LM, it does not appear. The cytoplasm of the cells contained abundant sER usually appears acidophilic.

![]() With EM, it appears as irregular network of membranous tubules and vesicles devoid of ribosomes in contrast to the flattened ribosome-studded cisternae of rER. The sER tubules may be continuous with those of rER and Golgi apparatus .

With EM, it appears as irregular network of membranous tubules and vesicles devoid of ribosomes in contrast to the flattened ribosome-studded cisternae of rER. The sER tubules may be continuous with those of rER and Golgi apparatus .

Functions

- Steroid hormone synthesis in the testicular interstitial cells, the cells of the corpus luteum and adrenal cortex cells.

- Drug detoxification in liver cells.

- Lipid synthesis in the intestinal absorptive cells.

- Release and storage of Ca ++ ions in striated muscle cells.

- Production of HCL in gastric parietal cells.

Golgi Apparatus (Golgi complex)

The Golgi apparatus is a membranous organelle concerned principally with synthesis, concentration, packaging and release of the secretory products.

With LM, it can be selectively stain with silver salts or osmium where it appears as a black network located near the nucleus. In H&E sections, it may be visible as a lighter-stained region called negative Golgi image . It is seen to great advantage in secretory cells such as osteoblasts.

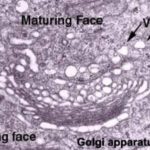

![]() With EM, the main structure unit of the Golgi apparatus is a flattened membranous vesicle called Golgi saccule.

With EM, the main structure unit of the Golgi apparatus is a flattened membranous vesicle called Golgi saccule.

The Golgi saccules are arranged in Golgi stacks that contain from 3-10 saccules. Most cell types possess several stacks of Golgi saccules forming an elaborate ramifying network termed the Golgi complex.

Each stack of saccules has 1) a forming face or Cis face that is convex in shape. 2) a maturing face or trance face that is concave. The Cis face is usually associated with a number of small transfer vesicles. The trance face characterized by being associated with much larger secretory granules .

Functions

- Packaging and concentration of secretions.

- Modification of the secretory products such as glycosylation and sulfation of proteins to for glycoproteins and sulfated glycoproteins (mucus).

- Production of primary lysosomes.

Lysosomes

They are membrane-bounded vesicles (0.2-0.4μm) containing a number (more than 40) of hydrolytic enzymes that are active at acid pH (acid hydrolases) maintained within their interior. This group of enzymes is capable of destroying all the major macromolecules (e.g., proteins and lipids) of the cells.

LM provides no direct evidence for the existence of lysosomes. The lysosomes are resolved at the LM level when their enzyme contents (e.g., acid phosphatase) are stained by histochemical methods.

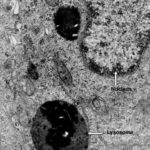

![]() With EM, The lysosomes appear as spherical membrane-bounded vacuoles with there contents showing varying degree of electron density.

With EM, The lysosomes appear as spherical membrane-bounded vacuoles with there contents showing varying degree of electron density.

Types of lysosomes

Primary lysosomes are lysosomes freshly formed from the Golgi or sER. They contain nothing but hydrolytic enzymes.

Secondary lysosomes formed as the result of fusion of primary lysosomes with phagosomes. A phagosome is a membrane-bounded vesicle containing either exogenous material (e.g., bacteria) and it is called heterophagosome or endogenous material (e.g., damaged organelle) and it is called autophagosome.

Multivesicular bodies are spherical forms of heterophagosomes. They are membrane-bounded vesicles containing a number of smaller vesicles.

Residual bodies are debris containing vacuoles representing the terminal stage of lysosomal activities. Their contents may either be extruded from the cell by exocytosis or accumulate in the cytoplasm as lipofuscin pigments.

Functions

- Degradation of any exogenous macromolecules (phagocytosis and pinocytosis).

- Disposition of any organelles or cell constituents that are no longer useful to the cell (autophagy).

Peroxisomes

Peroxisomes are spherical, membrane-bounded organelles containing peroxide forming enzymes and catalase that are involved in the formation and degradation of intracellular hydrogen peroxide.

With LM, it does not appear. ![]() With EM, they are membrane-bounded vacuoles, vary in size and appearance depending on species and cell types. They are relatively large in hepatocytes and kidney cells and small in intestinal cells (microperoxisomes).

With EM, they are membrane-bounded vacuoles, vary in size and appearance depending on species and cell types. They are relatively large in hepatocytes and kidney cells and small in intestinal cells (microperoxisomes).

In human cell, they contain finely granular matrix of moderate density. In many other species, they have crystalline core called a nucleoid.

Such nucleoid is absent from liver peroxisomes from reptiles, birds, and human being which are species that lack urate oxidase, an enzyme that degrades urates.

Functions

- Peroxisomes contain at least three oxidase (D-amino acid oxidase, urate oxidase and catalase).

- The D-amino acid oxidase, urate oxidases are responsible for the production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).

- The catalase then utilizes the H2O2 in oxidation (and therefor, detoxification) of various toxic substances such as phenol, alcohol and fatty acids.

- Non-membranous organelles

They are cytoplasmic organelles that possess no bounding membrane of their own. They include ribosomes, and centrioles.

Ribosomes

![]() They are rounded ribonucleoprotein particles, 20-30 nm in diameter that provide the intracellular sites where amino acids are linked together to form polypeptide chains (proteins).

They are rounded ribonucleoprotein particles, 20-30 nm in diameter that provide the intracellular sites where amino acids are linked together to form polypeptide chains (proteins).

With LM they are too small to be seen. However, cell containing abundant ribosomes usually has basophilic cytoplasm. Such cytoplasmic basophilia is largely due to the strong affinity of rRNA for hematoxylin.

![]() With EM, the ribosomes are seen free in the cytoplasm either as separate entities or attached to messenger RNA molecules in small aggregation called polyribosomes or polysomes. Polyribosomes may also be attached to the surface of rER.

With EM, the ribosomes are seen free in the cytoplasm either as separate entities or attached to messenger RNA molecules in small aggregation called polyribosomes or polysomes. Polyribosomes may also be attached to the surface of rER.

Each ribosome composed of a large and a small subunit that are made of rRNA and different types of proteins.

Functions

Free ribosomes are responsible for synthesis of proteins for internal use (cytoplasmic proteins and enzymes).

Attached ribosomes are responsible for synthesis of proteins for external use (secretory or lysosomal enzymes).

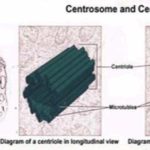

Centrosome and Centrioles

The centrosome is a specialized zone of cytoplasm contains a pair of centrioles together known as a diplosome, spherical bodies, procentrioles organizer and centriolar satellites that function as microtubular organization center.

With LM, the centrioles are selectively stained with iron hematoxylin where they appear as two tiny dots located close to the nucleus. In some epithelial cells,

centrioles are located in the apical cytoplasm immediately beneath the ciliated surface. Such apical centrioles are called basal bodies and from which cilia originate.

![]() With EM, each centriole is a hollow cylinder, closed at one end. The two centrioles of each diplosome are arranged with their long axes at right angles to each

With EM, each centriole is a hollow cylinder, closed at one end. The two centrioles of each diplosome are arranged with their long axes at right angles to each

other. The wall of each centriole is made up of nine triplet of parallel microtubules connected to each other by a fine filaments, the protein link.

Functions

- Formation of mitotic spindle during cell division.

- Microtubular organization center

- Ciliogenesis by the formation of procentrioles from the procentrioles organizer.

Cytoskeleton

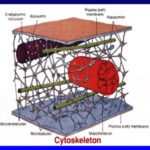

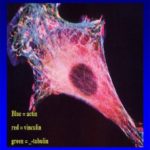

![]() The cytoskeleton is a complex network of minute filaments and tubules located within every cell, that maintain cell shape and stability and are responsible for some cell functions. It includes cytofilaments and microtubules.

The cytoskeleton is a complex network of minute filaments and tubules located within every cell, that maintain cell shape and stability and are responsible for some cell functions. It includes cytofilaments and microtubules.

Cytofilaments

![]() Cytofilaments are minute thread-like structures of three types:

Cytofilaments are minute thread-like structures of three types:

The Actin (thin filaments) is found in muscle cell, in the core of each microvillus, in motile cells such as macrophages and in developing nerve cells. Their diameter is about 5 nm.

The Myosin (thick filaments) occurs mainly in muscle cells in association with actin filaments. They have a diameter of 15 nm.

The Intermediate filaments are 10 nm in diameter and include neurofilaments in neurons, glial filaments in astrocytes and tonofilaments in epithelial cells.

Microtubules

They are hollow tubular structures of variable length with a constant diameter of 25nm. Microtubules are stable permanent structures in cilia, flagella, centrioles and basal bodies. Each microtubule is made up of protein molecules (tubulin) that appear to organize into protofilaments that run parallel to the length of the tubule. A total of 13 protofilaments comprise the wall of a microtubule.

Functions of the cytoskeleton

- It provides the structural support for the plasmalemma, cellular organelles and some cytosol enzyme system.

- It provides the means for the movement of intracellular organelles within the cytoplasm.

- It plays an essential role in cell motility as well as provides the framework of motile structures such as cilia and flagella.

- It is responsible for contractility of the muscle cells.

- It plays an important role in epithelial cell adhesion as well as cell division.

Cytoplasmic Inclusions

They are temporary lifeless accumulation of metabolites or cell products, such as stored food, pigments and crystals.

- Stored food

- Glycogen

- Lipids

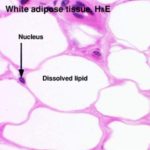

The fat cells of adipose tissues and the fat storing cells of the liver store the lipids. Routine processing generally extracts lipids from tissue and therefore, in H&E sections, lipid droplets within cells appear as unstained vacuoles ![]() .

.

Lipids are best demonstrated in frozen sections stained by specific lipid methods such as osmium or sudan III with which lipids are stained black and orange respectively.

- Pigments

They are substances that have their own color in their nature state.

- Exogenous pigments

The exogenous pigments are those that have been produced outside the body. They include carotenes, dusts, minerals and tattoo marks.

- Carotenes

Carotenes are a family of fat-soluble compound found in vegetable such as carrots, tomatoes and vegetable juice. When animals fed on carotene-containing vegetables, it colors its body fat yellow. Carotenes are provitamens and may be converted into vitamin A.

Ingestion of large amount of carotenes cause the skin of the body to appear yellow or even reddish color due to its great contents of carotenes. This condition is called carotenemia (increase carotene level in the blood). It might be confused with the more serious pathological condition called jaundice (caused by increase bilirubin level in the blood).

- Dusts

The lungs of heavy smokers usually blackened due to accumulation of carbon particles in the alveolar macrophages located in the wall of the lung alveoli.

- Minerals

Silver causes a gray pigmentation of the body. Lead can impart a blue line to the gum.

- Tattoo marks

They are inorganic pigments inserted deeply into the skin with needles.

The pigments are ingested by the subcutaneous macrophages and remain permanently within their cytoplasm.

- Endogenous pigments

They include hemoglobin, hemosiderin, bilirubin, melanin and lipofuscin.

- Hemoglobin

he hemoglobin is an iron-containing pigment of erythrocytes has the function of oxygen transport throughout the body.

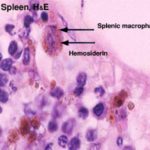

- Hemosiderin and bilirubin

They are formed as the result of degradation of old erythrocytes by the spleen macrophages. Hemoglobin is degraded into hemosiderin and bilirubin. The hemosiderin is a golden brown iron-containing pigment usually seen within the cytoplasm of the splenic macrophages ![]() .

.

The bilirubin is yellowish-brown pigment. It has to be removed from the blood stream by the liver and excreted in bile.

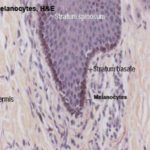

- Melanin

The melanin is a brown-to-black pigment presents in skin ![]() , hair and eyes. There is two type of melanin: eumelanin, which has a brownish black color, and phaeomelanin that has a reddish-yellow color .

, hair and eyes. There is two type of melanin: eumelanin, which has a brownish black color, and phaeomelanin that has a reddish-yellow color .

- Lipofuscin

The lipofuscin is a golden-brown intracellular pigment represents a normal product of organelle’s degradation. It accumulates with increasing age particularly in long-lived cells such as neurons and cardiac muscle cells (hence, they are referred to as age pigments or wear and tear pigments).

III. Crystals

Such as calcium oxalate and calcium carbonate crystals can be seen in the cytoplasm during certain disease conditions.

Nucleus

The nucleus is the archive of the cell that carries the genetic information necessary to regulate the different cell functions. It consists primarily of DNA (20% of its mass), DNA-binding proteins, and some RNA.

The DNA-binding proteins are of two major type histones and non-histones. The histones are involved in the folding of DNA strands and regulation of DNA activity. The non-histones are involved in the regulation of gene activity.

The nuclear RNA represents newly synthesized transfer and ribosomal RNA that has not yet passed into the cytoplasm.

With LM, the nuclei appear as basophilic structure located either centrally, eccentric or in a peripheral position. Most commonly nuclei are spherical or ovoid but they may be spindle-shaped (smooth muscle), bean or kidney-shaped (monocytes), or multilobulated (neutrophils).

Most often, cells are mononucleated. Some however, may be binucleated or even multinucleated.

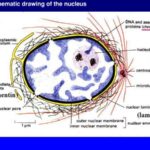

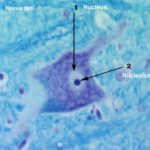

![]() The interphase (not engaged in cell division) nucleus consists of nuclear envelope, chromatin, nucleolus and nuclear sap (karyolymph).

The interphase (not engaged in cell division) nucleus consists of nuclear envelope, chromatin, nucleolus and nuclear sap (karyolymph).

- Nuclear envelope

With LM, it appears as a single basophilic line due to the presence of condensed chromatin adherent to its inner surface (peripheral chromatin) as well as ribosomes on the outer surface of the nuclear envelope.

![]() With EM, he nuclear envelope consists of two membranes separated by a perinuclear space 25nm wide.

With EM, he nuclear envelope consists of two membranes separated by a perinuclear space 25nm wide.

The outer membrane is continuous with the membranes of both the rER and sER and it may be studded with ribosomes. At the inner surface of the inner membrane, a layer of condensed chromatin known as granular lamina is usually encountered.

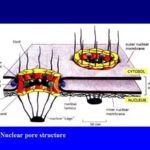

![]() Numerous pores through which the nucleus communicates with the cytoplasm interrupt the nuclear envelope. The nuclear pore is guarded by two annuli, an outer and an inner annulus, each with eight globular subunits 15-20 nm diameter, projecting inwards from them are eight radially arranged spokes. In the center of the pore there is a central granule or plug. Such structure is called nuclear pore complex.

Numerous pores through which the nucleus communicates with the cytoplasm interrupt the nuclear envelope. The nuclear pore is guarded by two annuli, an outer and an inner annulus, each with eight globular subunits 15-20 nm diameter, projecting inwards from them are eight radially arranged spokes. In the center of the pore there is a central granule or plug. Such structure is called nuclear pore complex.

- Chromatin

wo types of chromatin are distinguished: heterochromatin and euchromatin.

- Heterochromatin

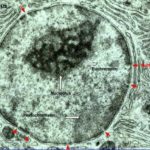

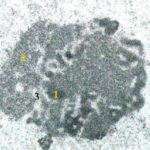

![]() The heterochromatins consist of tightly coiled portions of chromosomes. The genes are repressed and transcription does not occur. It predominates in inactive cells.

The heterochromatins consist of tightly coiled portions of chromosomes. The genes are repressed and transcription does not occur. It predominates in inactive cells.

With LM, they appear as fine and coarse basophilic granules scattered throughout the different regions of the nucleus.

With EM, it appears as electron-dense areas tend to be clumped around the periphery of the nucleus (peripheral chromatin), around the nucleolus (nucleolus associated chromatin) and also forms irregular clumps throughout the nucleus (chromatin islets).

In females, the inactive X-chromosome forms a small mass located at the edge of the nucleus and is called Barr body.

- Euchromatin

![]() The euchromatin is the extended, uncoiled portions of chromosomes in which the transcription of DNA is active. This type of chromatin is found in active cells. With LM, euchromatin is invisible because they are very thin and extended. With EM, they appear as electron-dense nuclear materials represent the parts of the DNA that are active in RNA synthesis.

The euchromatin is the extended, uncoiled portions of chromosomes in which the transcription of DNA is active. This type of chromatin is found in active cells. With LM, euchromatin is invisible because they are very thin and extended. With EM, they appear as electron-dense nuclear materials represent the parts of the DNA that are active in RNA synthesis.

- Nucleolus

It is a conspicuous, spherical, basophilic structure ![]() that is primary concerned with synthesis of ribosomal RNA.

that is primary concerned with synthesis of ribosomal RNA.

With LM, usually one, sometimes several nucleoli are seen. They are usually basophilic mainly due to nucleolus associated chromatin.

![]() With EM, the nucleolus consists of a sponge showing dark materials of granular (pars granulosa) and fibrillar (pars fibrosa) both form the nucleonema which is ribonucleoprotein permeated by dispersed filaments of DNA (pars amorpha).

With EM, the nucleolus consists of a sponge showing dark materials of granular (pars granulosa) and fibrillar (pars fibrosa) both form the nucleonema which is ribonucleoprotein permeated by dispersed filaments of DNA (pars amorpha).

The primary function of the nucleolus is the synthesis of ribosomal RNA (rRNA). The genes that code for rRNA are known as nucleolar genes that lie along five different pairs of chromosomes.

- Nuclear sap (karyolymph)

The nuclear sap is a colloidal solution in which chromatins are suspended. It helps in the movement of RNA (rRNA, tRNA, and mRNA) toward the nuclear pores.

The Cell Cycle

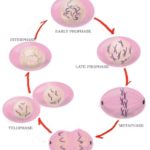

![]() The cell cycle is the alternation between mitosis and interphase. The interphase includes three stages; first gap stage, synthesis stage and second gap stage.

The cell cycle is the alternation between mitosis and interphase. The interphase includes three stages; first gap stage, synthesis stage and second gap stage.

The first gap stage (G1-stage) is the stage between the end of mitosis and the synthesis stage (S-stage). During this stage the RNA and protein synthesis occur and the cell volume is restored to its normal size.

During the synthesis stage (S-stage) the actual amount of DNA is duplicated. In the second gap (G2-stage) d-chromosomes are formed and the cell begins to enter cell division.

Cell division (mitosis)

The mitosis includes four different phases: prophase, metaphase, anaphase and telophase.

- Prophase

- Individualization of chromosomes.

- Initiation of mitotic spindle.

- Centriolar duplication

- Metaphase

- Disappearance of nuclear envelope.

- Chromosomes arranged in equatorial plate.

- Spindle complete.

- Disappearance of nuclei.

- Early anaphase

- Chromosomes split longitudinally and migrate to poles

- Late anaphase

- Cleavage furrow initiated and beginning of cell division.

- IRIS Readiris 11 Pro

- Macrabbit CSSEdit 2 MAC

- ARTS PDF Aerialist

- AutoCAD Structural Detailing 2015

- Pinnacle Studio 17 Ultimate

- Telophase

- Nucleolar reconstitution.

- Nuclear envelope formation.